Editor’s note: This essay is part of a series delivered monthly via email. If someone forwarded it to you, add your email here to receive future posts directly. If you already subscribe, please consider forwarding it—word of mouth is the best way to boost distribution.

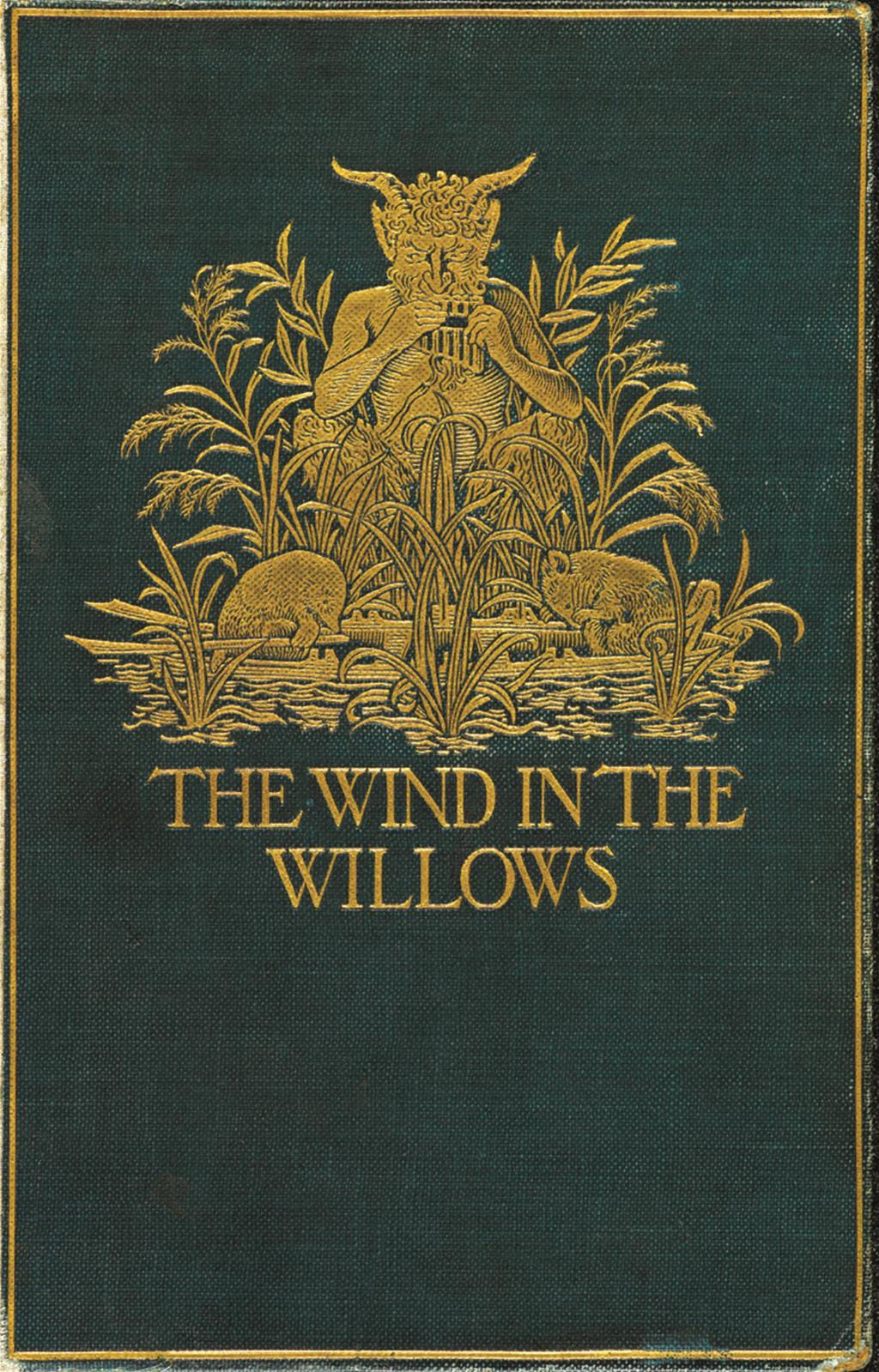

In “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn,” a chapter in The Wind in the Willows, the Mole and the Water Rat spend a summer night searching for a lost baby otter—boating downstream by moonlight until dawn—when strange music draws them to a mysterious island in the river.

On it, they find the otter pup sleeping at the hooves of Pan, lulled by the deity’s piping. Pan disappears as the sun’s first rays dazzle the animals, and they are left forgetful, questioning their own recollection of events like the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

It’s a scene that beautifully depicts the short, hot nights of late June, which are well-suited to adventure. But it also illustrates what critics have pointed to as a key difference between British and American children’s books: British writers aren’t afraid of mixing reality and fantasy in nature writing, while Americans treat nature as exhilarating or threatening—but usually, not magical.

Indigenous American cultures have acknowledged non-human spirits in nature through centuries of storytelling, but people in the Western scientific and literary tradition—especially in the U.S.—have been eager to overlook their own instinct to imbue animals and wild places with animistic souls and personalities that transcend the mundane.

Instead, we’ve been tempted to treat nature ever more clinically, for fear of being seen as frivolous if we make space for reverence—and sometimes, capricious humor—while seeking a deeper engagement with the natural world. But our tendency to want to do this as a way of making meaning is nevertheless reflected subtly in American English.

A few years ago, a friend gave me an old Audubon field guide from the mid-1940s. The book’s best feature is an index that lists hundreds of colloquial bird names, inviting readers familiar with names like “rain crow” for cuckoos, “coffin-bearer” for great black-backed gull, and “frost-bird” for American golden plover to look up a species by its official common name and learn more:

Call-up-a-storm, see common loon.

Corn-thief, see American crow.

Clicker, see yellow rail.

Ice partridge, see ivory gull.

Lilliputian, see winter wren.

Lady-of-the-waters, see tricolored heron.

Mother Carey’s chickens, see storm petrels.

Nonpareil, see painted bunting.

Timberdoodle, see American woodcock.

Whiskey jack, see Canada jay.

It’s wonderful to think about people using all of these names in common parlance, but one thing that struck me in particular was how often they invoked the sacred and/or the supernatural.

Fairy-duck, see phalaropes.

Good-god, see pileated woodpecker.

Lord-god, see ivory-billed woodpecker.

Nightwalker, see ovenbird.

Swamp-angel, see wood and hermit thrushes.

Water-witch, see grebes.

In Princess Mononoke, the Night-Walker is an enormous phosphorescent god who walks the forests and mountains of Muromachi-period Japan; an amusing juxtaposition with the tiny ovenbird, though both uses of the name inspire a sense of awe. Listening to the ethereal evening singing of hermit thrushes in the north woods, it’s also easy to understand why they were referred to as angels.

The lord-god bird, the most sublime of all, is gone of course—or perhaps, ascended to the land of dreams—for “man always kills the thing he loves, and we the pioneers have killed our wilderness,” as Aldo Leopold wrote in “The Green Lagoons,” about his exploration of the Colorado River delta before it was irrigated out of existence.

Others names from the book are lighter and funnier, still sounding like characters in fairy tales:

Burgomaster, see glaucous gull.

Big cranky, see great blue heron.

Frog-in-throat, see pied-billed grebe.

Gobbler, see wild turkey.

Meadow-wink, see bobolink.

Snowflake, see snow bunting.

One bird in particular—the American bittern—trumps all the others mentioned in the index for the number of amusing names it has inspired. It’s been called the bog bumper, dunkadoo, look-up, meadow hen, plum pudd’n, stake-driver, sun-gazer, thunder pumper, and water belcher.

The fact that people across North America once encountered bitterns at such a high rate that they could develop this level of familiarity with the bird and its habits—and trust that their neighbors would recognize them too (“Did you hear the dunkadoo this morning?” “Sure did!”)—itself feels like evidence of avifaunal decline.

The bittern is a remarkable bird in the heron family that lives in vast cattail marshes and wet meadows. Two of its names (“look-up” and “sun-gazer”) reflect its use of behavioral camouflage, standing perfectly still with its beak pointed skyward to blend in among the reeds. The others (except “meadow hen,” which refers to habitat, and possibly “stake-driver,” which may refer to its movements while calling) all describe the bird’s bizarre call, which sounds like … well, a bog bumper.

Bitterns today are no longer the stuff of small talk. They are rarely detected, and to have a good chance of encountering a bittern one needs to be out at dawn—or late in the evening—within earshot of a marsh.

Hearing one is a privilege, because bitterns are more than denizens of marshes: They are gatekeepers, in a way, and when they choose to reveal themselves, it means that they have granted the observer a more complete experience of the marsh, as a sacred space that is occupied by many other animate entities.

Whether the bittern’s powers exceed those that I can perceive—and whether there are other presences in the marsh that I cannot detect, because they are invisible or even phantasmal—is a question that does not cause me much anxiety.

Instead, I am satisfied to know that such experiences are what make life on Earth unique: There are rivers, after all, on other planets, but they consist only of flowing water. They are not haunted—even by gods and ghosts—and our glimpses of them through telescopes are the only moments in which they have even been beheld, much less pitied for their emptiness. ◆